Factors That Limit You

2023-03-17 Carl Riis

It’s a thinking kind of evening. The kind for making up your own mental models and pretending you’ve discovered universal truths. I highly recommend it.

Something many humans, myself included, love thinking about is how to become good at making ourselves do stuff. Trying to do stuff, however, can be depressing. This is because you almost always end up doing less stuff than you intended to. In this post, I try to cover the factors that limit you. Read it for discouragement or fun.

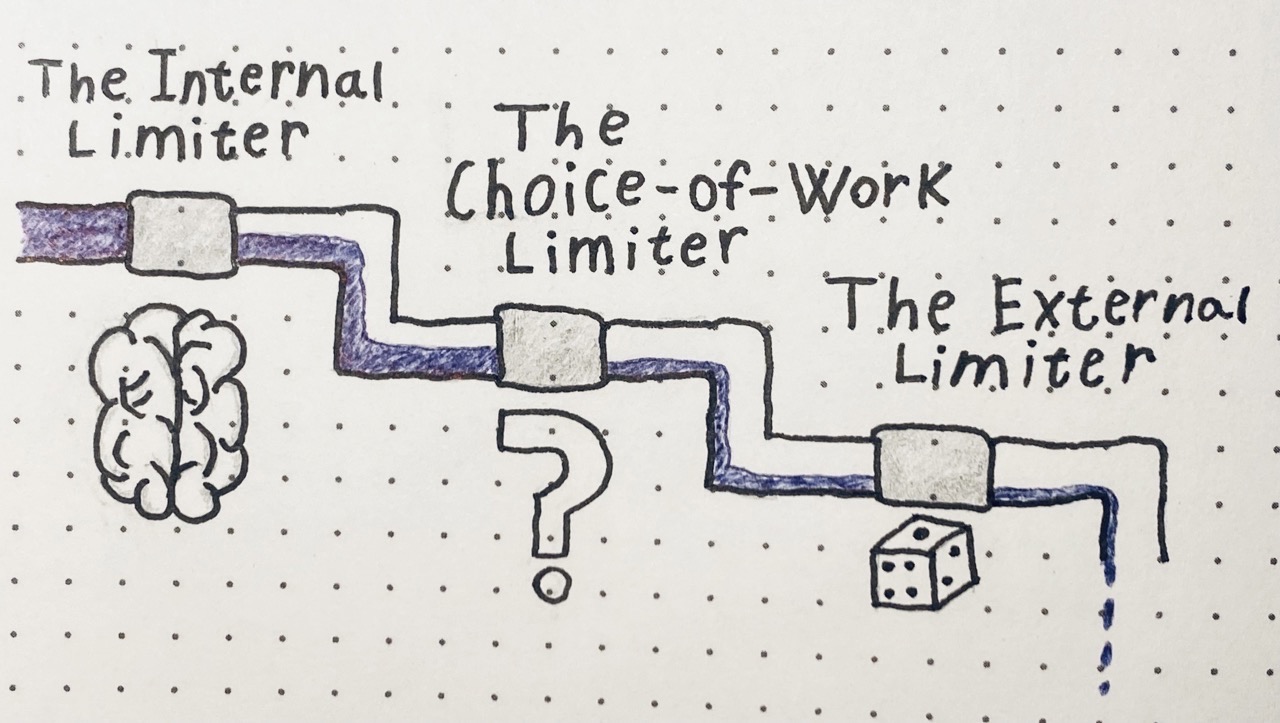

Let’s imagine a system of pipes. What flows in is our effort, and what flows out is effort realized. Along the way, water gets lost to different limiters. I’ll cover some of these limiters in this post.

The Internal Limiter

This is a bit of a meta factor. What flows in includes intention of effort, but what flows out is purely effort exerted. Some people might take issue with me allowing intention of effort as a valid input in our effort-in pipeline. To that I say, the effort of trying to make an effort is also effort. An example is trying hard to get some work done but getting distracted by clips on YouTube. You may have had high intent of effort, but the effort you ended up exerting towards your goal was low. This doesn’t mean you weren’t trying, however.

This limiter can be especially frustrating because it’s a limitation of oneself, which can make it tied to your feeling of self-worth. It’s easy to imagine everything you could achieve if you weren’t limited by yourself. It’s important to remember, however, that while easing this limitation can be a great advantage, it’s impossible to remove entirely. Some people are already at max capacity.

Strangely, the grip of the limiter might tighten the more effort and time your pour through it. You’ll likely find that you have to reserve periods where you completely cut off the stream of effort. This is also called “taking breaks”. It’s something I struggle to do myself. This is because, while the relationship between taking breaks and increased flow is clear, the exact increased flow gained from a break is hard to predict. This ambiguity makes them feel harder to justify.

The Choice-of-Work Limiter

You always have a choice of what to spend your time on. All this choice, however, is also a bit of a curse. Considering you’re trying to achieve something with your work, what you spend your time on will have a certain efficiency in achieving that goal. It’s reasonable to say that some of your work gets “lost” because you could have spent it on something more efficient.

Unlike the first limiter, this one is more shrouded in mystery. The efficiency of your current choice-of-work is not known to you. A choice of work that seems very efficient now can turn out to have been an inefficient choice years from now.

The External Limiter

Here we finally have a limiter that is beyond your control, the world. The world won’t always work in your favor. Unforeseen circumstances beyond your control can significantly slow down your progress. On the other hand, lucky unforeseen circumstances can also boost your progress. That’s to say; external stuff is unpredictable.

Conclusion

A very small amount of your intent of effort actually gets converted into usable realized effort. A reasonable, understandable response to this is to get very frustrated. Another approach is to push on regardless.

This is, oddly enough, one of the most important skills to acquire as a human - realizing the odds are stacked against you but trying anyway.

You should have enough compassion for yourself to forgive your inefficiencies and enough self-preservation to forgive the inefficiencies of the world.